In the aftermath of one of the biggest financial panics in history, Masaaki Shirakawa, the former Governor of the Bank of Japan, gave a somber speech at the Seminar of the Securities Analysts Association of Japan in Tokyo that resonated not only with those linked to Wall Street, but to everyone around the world who had felt the colossal weight of the Global Financial Crisis. He stated,

“One of the causes of the recent crisis was that concerned parties in the United States and Europe had not sufficiently learned the lessons from the bubble and financial crisis in Japan and the Asian financial crisis, so Japanese financial institutions might face similar problems in the future if they fail to sufficiently learn the lessons from the recent financial crisis in the United States and Europe.” (Shirakawa, 2009)2.

The statement, perhaps inadvertently, cast a shadow on one of the major monetary institutions, the Federal Reserve, and had echoed the sentiments of many at that time: perhaps it was time to reevaluate the framework of central banks?

Many had claimed that the Great Recession was caused by central banks unwittingly fueling the credit expansion that resulted in the crisis and demanded some sort of accountability from central banks. Accusations of central bank negligence in monitoring financial stability fueled calls for a reexamination of central bank independence, or the legal (de jure) framework that isolated banks from any sort of outside pressures or punitive actions by the government. Within the setting of a democratic state, many critics pointed to a quote by the famous economist Milton Friedman which was promulgated by Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in his book, 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to Covid-19, “it [is] intolerable ‘in a democracy to have so much power concentrated in a body free from any kind of direct, effective political control’” (Bernanke, 2022)3.

Central Banks are often tasked with one of three mandates: maintaining price stability (like the ECB), price stability and another objective, such as employment (the Dual Mandate of the Federal Reserve) or targeting exchange rates (such as the Hong Kong Monetary Authority). The theory behind central bank independence states that central bank independence leads to long term economic policy motivation, resulting in lower and more stable rates of inflation.

However, central banks are made up of governors and officials who are largely unelected and enact policy decisions with large distributional effects. How can unelected officials in modern democracies have so much concentrated power and discretion to affect prices and the purchasing power of their currency without any democratic oversight?

In the recent past, renown economist Art Laffer came out calling for the dissolvement of the Fed’s independence and for it to be entirely controlled by Congress and the President. Current Argentine President Javier Milei, during his election run, vowed to ‘burn down the Central Bank of Argentina’ in his economic shock therapy plan for Argentina.4

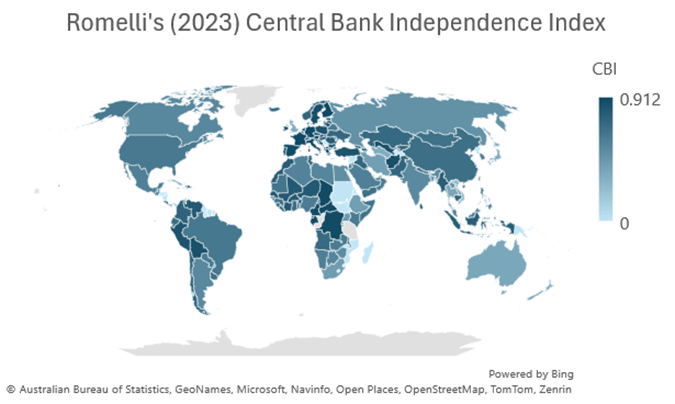

The concept of understanding Central Bank Independence did not start with the Great Financial Crisis. In 1992, Cukiermann, Webb, & Neyapti were the first successful pioneers in the field and developed an index in 1992 measuring CBI which was hailed as a breakthrough in economic literature5. Much work has been done in the past decades to accurately measure central bank independence (CBI) worldwide and its evolving role in financial markets and the real economy. One of the more recent public indices, constructed by Davide Romelli6, judged CBI on 6 distinct characteristics. Below is a map based on Romelli’s index showing the variation in CBI worldwide.

Figure 1:

His scale ranged from 0-1, with 0 being little to no independence while 1 being the highest independence.

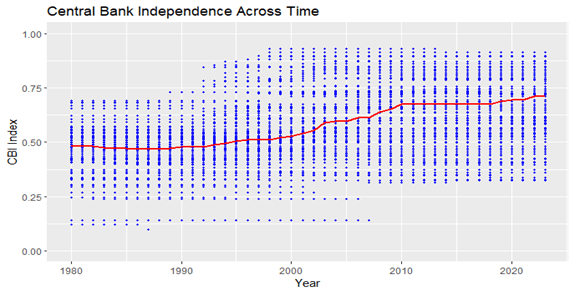

Figure 2 demonstrates how CBI has evolved over time. Each dot represents a nation with a central bank. As time passes, the data shows more and more countries granting their central banks higher indepdence.

Figure 2:

The collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1973 proved to be monumental for central banks. Now, instead of focusing on exchange rates, or the external value of their currency, central banks could now focus on price stability and the purchasing power of their currency within their domestic economy, or the internal value of their currency. Countries slowly began granting independence to their respective central banks, and following the Great Inflation scares of the 1980s, CBI experienced a renaissance where more CBs worldwide were granted independence. Using Romelli’s index, we can see how Central Bank Independence has increased globally over the years.

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic resurfaced the question of CBI in modern democracies. From generous fiscal stimulus packages spanning trillions of dollars, to supply constraints due to the war in Ukraine and conflicts in the Red Sea against Houthi militants, to demand shocks in advanced economies, to issues with repaying dollar denominated debt taken up by developing economies, central banks were faced with a mirage of problems in restoring price stability. For the first time since the Great Financial Crisis, many countries saw their governments at odds with their central banks, and often provided roadblocks for sound policy making.

Thus, the question I wanted to investigate was how did Central Bank Independence (CBI) influence central bank’s ability to maintain price stability during the Covid-Era (2019-2022)?

My research focused in this area specifically, and Table 7 is a snapshot from my paper, Harmony of Independence: Central Banks and the Inflation Waltz, showing my data-driven conclusion.

Figure 3:

| Table 7: Panel Regression of Inflation on CBIE Index during COVID ERA | |||

| Dep. Var: | |||

| Inflation | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| (Intercept) | 19.35** | 1.73** | 10.56*** |

| (5.02) | (0.79) | (2.82) | |

| CBIE Index | -16.94** | ||

| (7.13) | |||

| Interest Expense on Public Debt | 0.29*** | ||

| (0.08) | |||

| Lending Limit | -3.39 | ||

| (3.66) | |||

| Num.Obs. | 556 | 340 | 556 |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01The time period for this panel regression was 2019-2022. | |||

After a series of statistical tests, I concluded my research with a panel regression, regressing inflation on Romelli’s CBI on CPI inflation with controls for democratic ranking, capital openness, interest rate pegs, real GDP per capita, and trade.

The results in Table 7 show that countries with higher CBI index scores had greater price stability and lower inflation rates. Interest expense on public debt had a positive relationship with inflation. Thus, injecting fiscal stimulus and high government expenditure propped up inflation. Lastly, lending limit (or the ability of a government to receive funds from the central bank) had no statistical significance, implying that governments found other means to finance their aggressive fiscal stimulus packages.

The data shows that countries with higher CBIs were more successful in tackling inflation and maintaining price stability, allowing for a functioning economy. However, the democratic dilemma remains: In what ways can we grant central banks higher levels of independence while ensuring they are democratic institutions?

No country has yet found the perfect solution to balancing contemporary democratic ideals and an independent central bank. However, most institutions have settled on a middle ground- increasing transparency. A major breakthrough was seen shortly after the 2008 financial crisis with the passing of the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act which forced the Federal Reserve to disclose details about its emergency lending during the financial shock.

Each democratic state has its own unique approach to mitigating democratic ideals with an isolated central bank. Transparency is one key factor in bridging the gap and dispelling much of the associated mystery with the banks’ decisions among many other amendments. As those monetary institutions evolve in economies around the world, we will see more discussion about their role in our democracies and the power they exert.

Appendix:

- Featured Image for this article was generated by ChatGPT. Citation: OpenAI. (2024). Central Bank Independence (generated by ChatGPT). Retrieved from OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

- Speech by Mr. Masaaki Shirakawa, Governor of the Bank of Japan, at the Seminar of the Securities Analysts Association of Japan, Tokyo, 22 December 2009. r091223a.pdf (bis.org)

- Bernanke, B. S. (2022). 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19. WW Norton & Company.

- Sindreu, J. (2023, December 13). Argentina’s Milei swaps burning down the central bank for shock therapy. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/argentinas-milei-swaps-burning-down-the-central-bank-for-shock-therapy-101-460909a2?msockid=2fe052ffee0166da2e6441adefb667e8

- Cukierman, Alex, Steven B. Webb, and Bilin Neyapti. (1992) Measuring the Independence of Central Banks and Its Effect on Policy Outcome. The World Bank Economic Review 6:353-98.

- Romelli, D. (2022). The political economy of reforms in Central Bank design: evidence from a new dataset. Economic Policy, 37(112), 641-688.

Leave a comment