No idea is so outlandish it should not be considered

-Winston Churchill

Introduction:

The Bank of England, like other central banks worldwide, has been tackling the final stretch of the prolonged inflation battle triggered by the post-Covid inflation surge. However, unlike its counterparts, the Bank has kept its key effective borrowing rate (SONIA) significantly higher than those set by the Federal Reserve and the ECB. Despite the divergence in monetary policy and setting key rates, what has truly captured global attention is the intense standoff between the government’s policymaking branches. Chancellor Reeves announced ambitious tax hikes throughout this year to fill the holes in the national budget which has sent government borrowing costs higher than their 2008 levels and massive uncertainty in the bond market paired with forecasts of the UK entering stagflation. Meanwhile, Parliament and the Labor Party have been under pressure to deal with the stagnating economy and to take the government initiative to inject stimulus into the economy. With the BoE having their hands tied in slowing down the economy to regain control over inflation, Chancellor Reeves ensuring a balanced budget via higher taxes, and a frozen parliament, policymakers have encountered a stalemate in guiding the economy to a successful recovery.

Current UK Economic Outlook

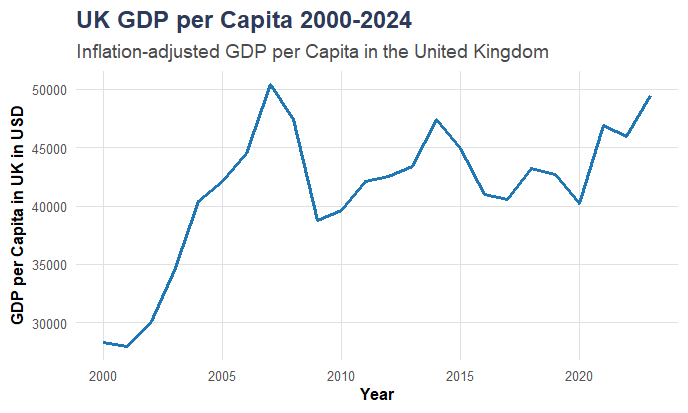

The UK economy has shown massive resiliency in the face of a multitude of negative economic shocks over the last decade and a half, with the UK economy growing and GDP figures showing an upward trend. However, despite showing strong GDP growth, when accounting for population growth, the numbers show a different story. Below, adjusted GDP per Capita for the UK from 2000-2024 is plotted.

Figure 1

GDP per capita is a useful indicator for showing economic stagnation since it accounts for both total output and population growth to show individual prosperity. GDP per capita was rising strongly until the Great Financial Crisis, however, post-crisis, it has taken over 15 years for an individual to be at the level of economic wellbeing they were before the crisis, and for more than a decade those in the UK were seeing lower average income levels.

This chart also shows an alarming reality. The UK has been stuck in a low growth equilibrium state, which attests to weak investment, less innovation and productivity, and low wages. We can infer that productivity, a key factor in determining long-term wage growth, has been stagnant.

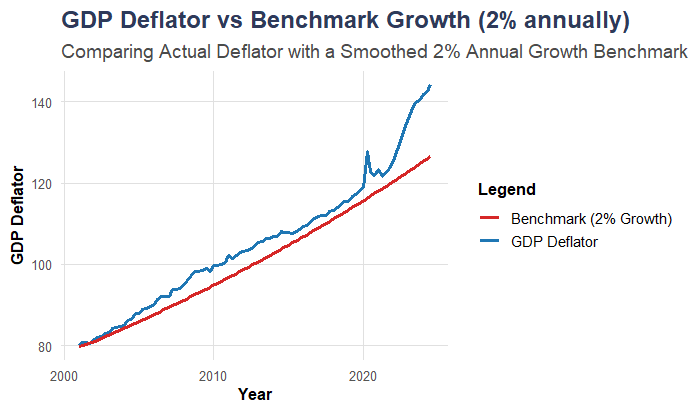

Below, Figure 2 observes how the price level has changed in comparison with a trend line showing the targeted 2% increase in the price level that the Bank of England has announced as their policy objective.

Figure 2

The figure shows that the rise in the price level has remained steadily above the targeted 2% growth, before completely deviating after 2022. If GDP per capita stagnates while inflation rises at this rate, real incomes fall, meaning consumers can afford less despite overall GDP growth. Such figures are rarely observed, but it is crucial for understanding why people feel worse off even when headlines show GDP growing.

Figure 3

Productivity is a key driver in real wage growth and overall economic growth in the long term. Figure 3 observes productivity change across all regions in the UK from 1998-2022. The data shows ever-growing regional inequality between regions, and when aggregated nationally, average productivity has hardly budged. Such low productivity growth should send alarm bells, signaling a low growth equilibrium. Thus, low UK productivity has made it harder to sustain fiscal expansion without raising inflation.

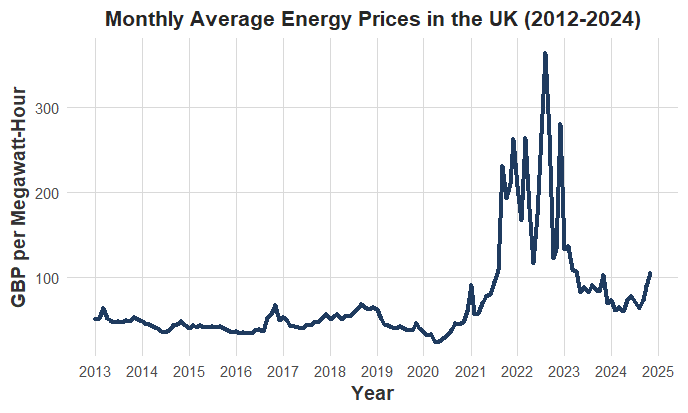

Many potential hypotheses can be put forward to pinpoint the low productivity nationally. However, higher costs for firms and weaker demand can impact productivity negatively. Figure 4 below addresses some of the new operating costs borne by firms that are passed on to consumers, making inflation persistent.

Figure 4

Figure 4 shows the volatility of energy prices in the UK from 2013-2025. Energy prices remained relatively stable, until skyrocketing from 2021-2023 and then coming down. However, upon closer inspection, the numbers show that energy prices in 2025 are now over twice what they were in 2020 and are continuing to grow. Such growth in energy prices, more than doubling in 4 years, increased firm operating costs and a reduction in consumer spending. Due to higher energy costs, most sectors, including services, will decrease operating hours and hire less, leading to a lower productivity spiral. On a macro level, lower productivity within firms will lead to a higher GDP-Debt burden for the UK. High energy volatility and rising prices expose the economy to supply shocks, and the ever-looming threats of tariffs can impact the UK economy more. Greater exposure to supply shocks can complicate monetary policy: what part of inflation is due to supply shocks?

What percentage is due to demand? These questions might throw dirt in the eyes of policymakers in the BoE.

Finally, Chancellor Reeves’ national insurance premium for businesses has increased hiring costs for firms. Combined with high energy prices and fiscal taxes, these shocks might create a “floor” for inflation that the BoE might not be able to break.

What Is Nominal GDP Targeting?

Nominal GDP Targeting has picked up speed within academia in the United States as a viable substitute for the Federal Reserve’s FAIT framework to be considered in the upcoming framework review. NGDP targeting focuses on two factors (inflation and real GDP) to stabilize the growth of total nominal GDP. Central banks targeting NGDP and guiding the total money value of the economy implicitly seek to stabilize the growth rate of nominal income and nominal spending by aiming to stabilize the total dollar (or Great British Pound) size in the economy.

With an NGDP target, its robustness allows for a symmetrical response to shocks and a balanced approach by monetary policy. For example, if real GDP growth slows due to a recession, NGDP targeting allows higher inflation to compensate, preventing deflationary spirals. On the other hand, if real GDP surges due to a productivity boom, NGDP targeting allows inflation to fall instead of forcing unnecessary monetary expansion. Thus, a central bank does not need to worry about which percentage is supply side or demand side; its robust framework allows the economy to stay on its general trend and see through transitory inflation.

Lastly, by establishing an explicit growth target, it creates an investment friendly economy due to macroeconomic stabilization.

Key Advantages of NGDP for the UK

The Bank of England adopting Nominal GDP Targeting has 3 distinct advantages and falls in line with their government mandate of price stability within the UK.

Encourages Long Term Investment & Productivity Growth

Firstly, NGDP targeting encourages long term investment. It avoids short term focus, increases economic stability, and anchors long term inflation expectations. Furthermore, it aligns better with debt sustainability by encouraging productivity and setting long-term growth targets. Investment in public infrastructure will also benefit, as in the case of the NHS. NHS spending relies on government funding, which is influenced by real GDP growth and tax revenue. Under inflation targeting, recessions can worsen public service funding gaps as revenues fall and borrowing costs rise. Thus, short-term economic downturns can have long-lasting consequences.

Reduces the Risk of Policy Misinterpretation

One challenge for monetary policy is constantly distinguishing between cost pull and demand push inflation. Inflation targeting (under FAIT or FIT framework) sometimes misinterprets low inflation due to productivity gains as weak demand, leading to unnecessary monetary easing that distorts capital allocation. As Scott Sumner remarked in his paper, “Inflation does not represent the resources that firms have to pay nominal wages to employees, nor does it represent the revenue that people and firms have available to repay nominal debts. In both cases, NGDP is the best variable that measures whether there is equilibrium in the labor market and in the financial markets1.” Under an inflation target, the Bank of England may misinterpret inflation readings.

Supports Real Wage Growth

Finally, NGDP targeting supports real wage growth. As seen in Figure 1, Real GDP per capita has only returned to its 2007 level after over 15 years. Moreover, NGDP is a more flexible framework that accommodates productivity without raising inflation.

Conclusion: UK Monetary-Fiscal Tensions: 1 Size for All?

The main goal of monetary policy should be to correct market failure. Nominal GDP Targeting is the perfect policy mix where the Bank of England it able to fulfill its mandate by price stability, Parliament can invoke growth-centered policies, and under the conceptual framework of the Laffer Curve, a higher GDP and growth will allow the UK Treasury to bring in the necessary funds to stabilize its sovereign debt obligations. The Bank of England is known for its innovative approaches to uncertain macroeconomics circumstances, and adding a NGDP target will be a welcomed chapter.

Appendix

- Sumner, Scott. “An Effective Monetary Policy with Nominal GDP Level Targeting.” Mercatus Center, 10 Dec. 2024, http://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/effective-monetary-policy-nominal-gdp-level-targeting.

Leave a comment