The solemn news that flooded out of the halls of the House of Commons in the morning of March 26, 2025 had the UK holding its breath. Amid the large welfare cuts, there were no announced tax hikes in the Spring Budget, but Chancellor Reeves and the Treasury foreshadowed another round of tax hikes similar to those of the Autumn Budget of 2024 looming in the future.

The UK, along with every G20 government, had ramped up large government deficits to guide the nation through the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigate its lingering effects. Now, Chancellor Reeves has unleashed a wave of austerity measures in an attempt to finally rebalance the government budget and hopefully put the fiscal deficit back on a sustainable track.

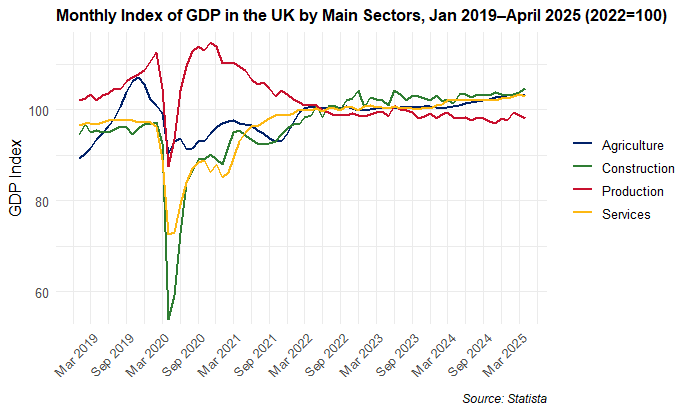

Some economies, most notably the US economy, bounced back quickly thanks to directed and well supported fiscal support policies. Thus, many credit that the V-shaped recovery of the US economy was mainly due to the fiscal support offered by the US Congress. However, other economies, most notably those in the European Monetary Union (EMU), are seeing a slower, stagnate recovery. The UK initially had had a fast recovery from the pandemic and outperformed its German and French counterparts. However, the momentum has seemed to have stalled. Since March 2022, the economy has grown at a snail-like pace.

Figure 1:

In a way, this is an echo of not-so-far history. After the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the UK bounced back, but underwent a decade of near-zero growth. In December 2019, the Royal Statistic Society commented that the low productivity growth in the UK since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 was the statistic of the decade and “reflects the significance of the unusual weak observed since the 2008 economic downturn.1”

After a decade of stagnant productivity growth and now the lethargic post-pandemic growth, alarm bells are sounding in the UK. The ever-looming possibility that the UK economy may enter a period of fiscal stagnation, a prolonged period of sluggish economic growth crippled by high public debt and fiscal distortions, seems to be a likely scenario. Combined with public infrastructure underinvestment, austerity measures, and higher taxes, the economy can plunge itself into the inescapable territories of low-growth equilibriums found in so many endogenous growth models.

Endogenous Growth & Hysteresis

The literature of endogenous growth highlights the impact of investment in human capital, innovation, and technology as key drivers of long-term economic growth. These variables shape the future trajectory and the pace at which the economy grows. Economies which perform poorly in these areas due to either political or financial pressures may end up in a low growth equilibrium trap or even a Malthusian trap. Endogenous models, such as the AK, Romer, and Galor-Zeira models, build upon these assumptions.

The general idea is that when an economy faces a severe recession or even a depression, output does not automatically rebound to its prior trend. One of the many economic theories that seek to rationalize the behavior of the economy under such pervasive conditions is Hysteresis. The cornerstone foundation of the theoretical notion of Hysteresis is that exogenous negative supply shocks can have scarring and persistent effects on unemployment and pushes economic growth downward. If weak demand is not mitigated quickly and efficiently, either through fiscal stimulus or accommodating monetary policy, expectations of prolonged stagnation may take hold. In response to future expectations of a weak economy, skill accumulation by workers will decrease due to falling wage premia along with R&D and business investment into capital expansion and innovation. Consumer and business sentiment falls along with productivity, a key factor of growth. The erosion of private sector confidence, combined with insufficient fiscal response, entrenches economic growth into very low levels.2 In the case of the UK, public underinvestment, rising taxes, and increased energy costs are leaving scarring effects and will have downside effects on economic growth if not mitigated.

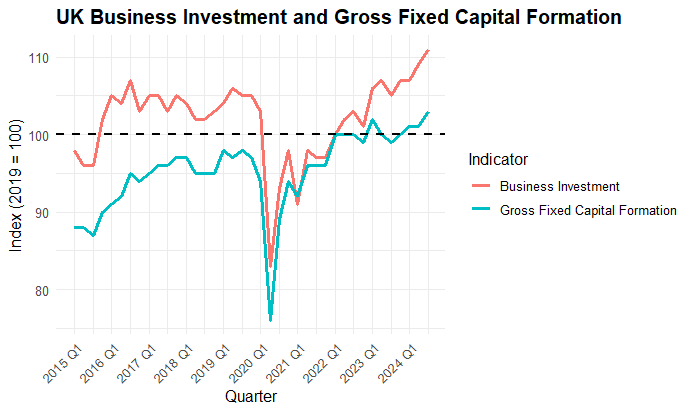

Figure 2:

Figure 2 shows low business and capital formation investment experienced in the UK economy over a span of 9 years. Despite the volatility induced by the Covid-19 pandemic, business investment has been stagnant for almost a decade while gross fixed capital formation has lagged. Business investment only surpassed its 2016 level in 2023 and overall growth from the time period has been near-zero. When firms realize that the economy is in a state of low growth and the targeted client base has weak demand for their services, they have little incentive to invest and build up future production capacity. In such a manner, weak internal demand translates into low investment and low productivity. If the tides change and the economy is able to finally expand and escape the low growth trap, firms do not have the production capacity to capitalize in the now-booming economy and expand their operations.

Dr. Peter Howitt, Professor of Economics at Brown University, remarked that “because many innovations result from R&D expenditures undertaken by profit-seeking firms, economic policies with respect to trade, competition, education, taxes and intellectual property can influence the rate of innovation by affecting the private costs and benefits of doing R&D3.” Thus, pro-growth policies need to address the demand for innovation and business expansion to have a pronounced effect on the economy. However, if austerity measures are introduced after every downturn in the business cycle, aggregate demand may never recover to pre-downturn levels and the private costs of R&D rise.

Furthermore, institutional changes can also deter domestic investment in the UK economy. A recent Financial Times article, Pension and housing policy is a war on Britain’s young, explores a deep lying issue underneath layers of regulatory carpet. Over the last 2 decades, regulators have forced pension funds to liquidate their investment in UK domestic companies and convert their portfolios into a myriad of UK government gilts (bonds). UK companies, long reliant on the investment of pension funds for long-term domestic capital, have relocated overseas to search for foreign funding. Many may point figures at British workers exhibiting “low productivity”, but ultimately domestic investment in innovation and growth governs the growth trajectory of the UK economy.

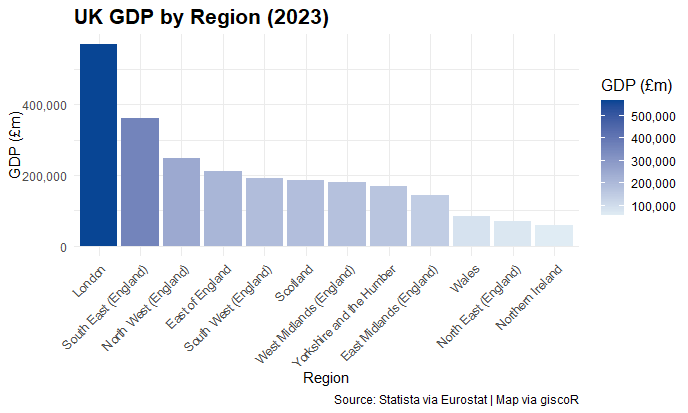

Figure 3:

In an environment of weak aggregate demand, the few regions that experience higher levels of productivity exacerbate regional inequality. Firms will tailor their business services to the needs of the more productive region, while skilled workers will emigrate from low productive regions to higher productive regions. Such agglomeration of productivity and high skilled workers will push the productive region forward, while other regions experience “brain drain” and lag behind. Figure 3 highlights the stark regional inequality within the UK. London, a well-known international hub of the world’s top talent, by far is the greatest regional economy, but other regions dominated by the metropolitan domestic hubs of Manchester and Birmingham don’t even measure half of London’s capacity (the Southeast Region of the UK may be experiencing spillover effects from London’s economy.)

Observing such unequal economic regional distribution, Stansbury, Turner, & Balls (2023)4, find that “UK’s cities – outside of a handful of Southern exceptions, most notably London – do not appear to benefit from the agglomeration economies seen in other industrialised countries, where scale and population density are strongly associated with higher productivity.” Such an exception will have consequences for higher regional unemployment, infrastructure underutilization, and the growing share of regional inequality. They further expand the notion of regional inequality by providing evidence that businesses outside of London experience significantly less opportunities for growth and scaling. Stansbury, Turner, & Balls (2023) find in their report that “SMEs in the North of England and the Midlands are substantially less likely to receive equity financing than observably equivalent firms in London.” If firms are not able to receive equity financing while costs increase due to the recent rising energy costs and increased National Employment Premiums, business will have limited means to expand operations. While firms in London and the Southeast may experience more generous equity financing and smoother operating costs, businesses in other regions of the UK see ever-mounting pressures and roadblocks in their day-to-day operations.

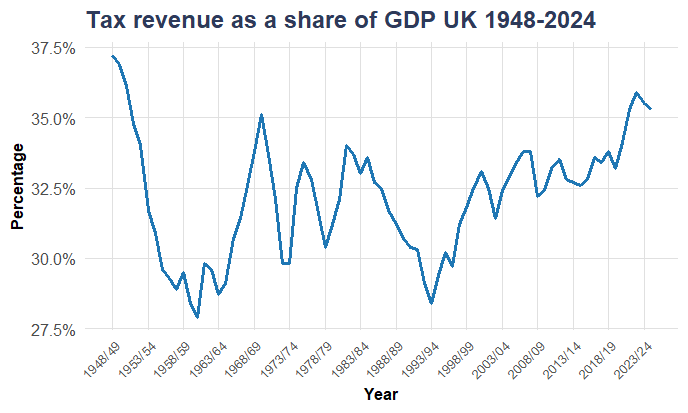

Figure 4:

Figure 4 shows how tax revenue has risen to levels not seen since the end of WW2. A few reasons can help explain the rise of Tax Revenue as a share of GDP since the early 1990s, particularly due to tax rates increasing, income distribution changes, and growth in sectors that are highly taxed (e.g. finance due to London’s booming Canary Wharf.)

The Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute & Brookings Institution assert that “tax reductions can also have negative supply effects. If a cut increases workers’ after-tax income, some may choose to work less and take more leisure. This “income effect” pushes against the “substitution effect,” in which lower tax rates at the margin increase the financial reward of working.”5 Taxes translate into decreased incentives for real productivity growth and economic expansion. With high tax rates, sectors that have potential to expand are discouraged while small and medium businesses are slowly priced out. Paired with the previously mentioned point that SME’s in the North and West Midlands are less likely to receive equity finance than their counterparts in London, burdensome tax policy can produce a considerable deadweight to those regions lagging behind.

If GDP growth remains static, rising taxes can have a crippling effect by reducing the effective nominal amount of GBP in the economy. Higher taxes reduce GDP growth, and if the BoE does not respond with easing the overbank rate, GDP growth can find itself at near-0 levels.

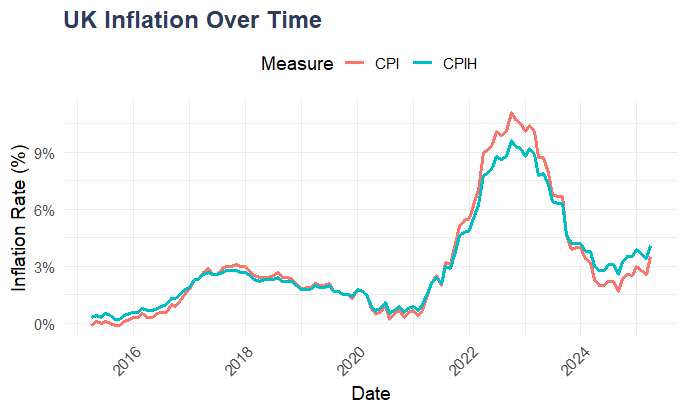

Figure 5:

Surprisingly, mainstream macroeconomic literature tends to separate the study of business cycles, management of aggregate demand, and the determinants of long-run productivity growth. However, understanding the intertwining relationship between each of these fields are necessary to understand the needs of the economy and how to avoid the stagnation trap. Supply shocks and growing taxes on businesses introduce increases in marginal costs for firms, generating upward pressures on prices and diminishing productivity. With higher costs, inflation may become entrenched as firms must increase their markups. After the succession of tax hikes in the Autumn Budget of 2024 and proposed tax hikes by the UK Treasury in the Autumn Budget 2025, we see UK inflation on an upward path. Paired with contractionary monetary policy, stagflation quickly becomes a reality. In The Scars of Supply Shocks: Implications for Monetary Policy by Luca Fornaro and Martin Wolf6, the study iterate this point and explains that

“Monetary tightening causes a reduction in inflation on impact. In the medium run, however, the monetary tightening becomes self-defeating. In fact, the productivity scars associated with tight money eventually push inflation above its value under the neutral policy… Not only a monetary tightening is likely to lead to lower investment and productivity growth, but it may also fail to mitigate significantly inflation in the medium run.” As we see in the data, inflation has decreased enormously from its COVID high, but has recently been on an upward trajectory. Weak productivity growth translates into higher marginal costs which will be passed through and generate inflation.

Luca Fornaro and Martin Wolf continue their argument by further emphasizing the impact of scarring effects introduced by supply shocks. They argue that these long “Scarring effects also tend to amplify the inflationary impact of supply disruptions and make it more persistent. Monetary tightening may backfire by depressing productivity growth and increasing inflation in the medium run.”

According to the Keynesian approach, inflation ultimately is consistent with firms’ inflation expectations and the real marginal cost to create goods. If there is an increase in the real marginal costs for firms, inflation increases as the increase in the marginal costs decreases firms’ markup. Expanding on the Keynesian approach, the role of monetary policy is to stabilize real marginal costs consistent with firms’ desired markup and to remove the incentive for firms to adjust their prices. The literature attributes that inflation is due to firms’ marginal costs, rather than growing demand as the Neoclassicals would say. However, the main problems facing British SMEs are far from being solved by monetary policy alone without directed intervention from fiscal policy. These problems hinder greatly the Bank of England’s ability to ensure price stability, and as Fornaro and Wolf explain, there is a rise in ‘medium-term’ inflation.

Conclusion

There is no one size-fits-all easy policy solution to deal with these issues. Fiscal authorities must create direct channels through which stimulus flows to firms and consumers during economic downturns and avoid austerity measured in order to maintain R&D, innovation, and productivity growth. Raising taxes on an already motionless economy won’t save the government from its overwhelming budget deficits. If anything, the only thing it would do will buy the government officials some time. As seen by the policies of Chancellor Reeves, the time saved by cutting welfare and invoking austerity measures is just but a few months. Meanwhile, the UK economy continues to stagnate. The Laffer Curve shows that after crossing the inflection point, increases in the tax rate will effectively not raise revenues. With UK GDP growing by 0.4% and 0.9% in 2023 and 2024 respectively, future tax hikes seem pointless. Simply put, one cannot tax the economy into growth. Though counterintuitive, by lowering taxes and spurring government investment into the domestic economy, there is a strong possibility that the economy can slowly outgrow mounting fiscal deficits.

Works Cited:

- Campbell, Richard. “Labour Productivity, UK: October to December 2019.” Labour Productivity, UK – Office for National Statistics, Office for National Statistics, 6 Apr. 2020, http://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/labourproductivity/bulletins/labourproductivity/latest.

- Macromusing Podcast run by David Beckworth at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3dObq7tXDuGFuYhfD6MrFg?si=bW0bYk-MT7KzKrwnyKAOyw - Howitt, Peter. “Endogenous Growth.” Endogenous Growth , http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Economics/Faculty/Peter_Howitt/publication/endogenous.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2025.

- “How Do Taxes Affect the Economy in the Long Run?” Tax Policy Center, taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-do-taxes-affect-economy-long-run. Accessed 1 July 2025.

- Stansbury, A., Turner, D., & Balls, E. (2023). Tackling the UK’s regional economic inequality: Binding constraints and avenues for policy intervention. Contemporary Social Science, 18(3-4), 318-356.

- Fornaro, L., & Wolf, M. (2023). The scars of supply shocks: Implications for monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 140, S18-S36.

Leave a comment